History of Thirty-eighth Regiment, The 9th Pennsylvania Reserves.

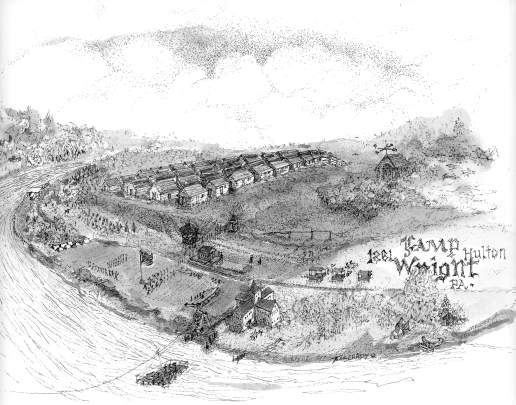

The Ninth Pennsylvania Reserves was organized at Camp Wright, near Pittsburg, on the 28th of June 1861, under the direction of General M’Call. Eight of the companies composing it were recruited in Allegheny County; one in Crawford, and one in Beaver. At the time of its organization there were over forty companies in camp, recruited in the western part of the State, under the call for seventy-five thousand men. The companies included in this regiment had been in camp from the early part of May and had been studiously drilled in elementary tactics. The election for field officers resulted in the choice of Conrad F. Jackson, Colonel; Robert Anderson, Lieutenant Colonel, and James M’Kinney Snodgrass, Major. The two formers had seen service in the Mexican war. The latter was at the time Major General of the Eighteenth division of the State militia. The men generally had had no previous military experience. Immediately after its organization, the officers commenced a regular series of regimental and officers’ drills, by which it was brought to a good degree of discipline.

On the 22d of July, the regiment was ordered to Washington. Leaving Pittsburg on the 23rd, it proceeded to Harrisburg, where it was supplied with arms and equipment, and from thence proceeded to its destination, arriving at daylight of the 26th. Bivouacking a half mile east of the Capitol till evening, it marched to Seventh street road, a distance of two miles, where it established its first camp. On the 28th the regiment was mustered into the United States service. Remaining in the camp until the 5th of August, it was moved to Tennallytown, where was established the general camp of rendezvous for the Reserves, under the command of General McCall. Here was established a regular routine of camp and picket duties, and details of parties to work on the fortifications in the vicinity. Major Snodgrass was assigned to superintend the construction of what was afterward named Fort Gaines, and continued there until the work was ready to receive its armament. From the 9th to the 16th of September the regiment was on picket duty at Great Falls, several miles up the Potomac. Here the rebels were for the first time encountered, holding the opposite bank. As opportunity offered they sent their leaden compliments across, which were promptly acknowledged. This exchange of civilities continued daily. On the 21st of September, the Harper’s Ferry smooth-bore muskets and the equipment received at Harrisburg were exchanged for new Springfield rifled muskets and complete equipment, by the entire regiment, except company A, which was armed with Sharp’s rifles, the private property of the men. On the same day, it was reviewed by General McClellan, accompanied by his staff, General M’Call, and staff, Governor Curtin and suite, the Secretary of War, and others.

On the 9th of October, the regiment broke camp at Tenallytown, and marching by the chain bridge, crossed into Virginia, and occupied a position near Langley, in line with the army of the Potomac, on its extreme right. Here the division went into winter quarters, and the discipline was made more stringent than before, as the enemy was supposed to be in the immediate front. In the organization of the corps which was here made, the Ninth was assigned to the Third Brigade, commanded by Colonel M’Calmont.1 A school for regimental officers was established for the brigade, which was regularly attended, and which, with the schools in the different regiments for company officers, was of great service in the establishment of discipline and in preparation for successful maneuvering in the presence of the enemy. On the evening of the 19th of November, orders were received from Headquarters directing Major Snodgrass to proceed, with five companies of the Ninth Regiment, to make a reconnaissance of the enemy’s lines in the neighborhood of Hunter’s Mills, eight miles in front of our line. Information had that day been received that the rebels were engaged in advancing their lines, and as a review was to be held on the following day, it was deemed advisable to verify the rumor. Accordingly, at ten o’clock that night, taking companies A, B, D, F, and G, with a guide, and two mounted orderlies, the Major proceeded to the locality indicated and made a thorough examination of their position. Finding them unchanged, he returned and reported the result, arriving soon after daylight. Scarcely had the detachment come within our lines, when a body of rebel cavalry was discovered on its trail, but too late to do any harm.

On the 20th of December, General E. O. C. Ord, who had succeeded Colonel M’Calmont in the command of the brigade, was ordered by General M’Call to proceed with his command to Dranesville, for the double purpose of securing forage, and driving back the enemy’s pickets. At two o’clock P. M., near Dranesville, a considerable body of the enemy was met, and as the Ninth Regiment was on the right of our column, it was soon briskly engaged. When first encountered his line was concealed from view by a thick wood, and considerable doubt existed whether the troops, which were now within sixty or seventy paces, were friends or foes. The men were impatient to fire and Colonel Jackson could with difficulty restrain them; an officer of the regiment had reported that they were the Bucktails, and the Colonel, that he might avoid the fatal error of killing our own men, was determined not to attack until he knew whom he was fighting. The impression that the Bucktails were in front was strengthened by one of the enemies calling out “don’t fire on us.” One of our men imprudently asked, “are you Bucktails?” the answer was, “yes, we are the Bucktails, don’t fire.”2 Nor did they fire until they received a full volley from the rebel line. The order was then given to open, and the action soon became spirited. After posting the artillery General Ord gave the word to advance, “Kane at the head of his regiment leading. His and Jackson’s regiments required no urging.”3 The enemy was soon routed and the victory was complete. General McCall, who came upon the field in the midst of the engagement, says, “Here was the Ninth Infantry, Colonel Jackson, who had gallantly met the enemy at close quarters, and nobly sustained the credit of the State. * * * The number of killed found in front of the position occupied by the Ninth Infantry, Colonel Jackson, is, in my estimation, proof enough of the gallantry and discipline of that fine regiment.” The loss was two enlisted men killed, and two officers and eighteen enlisted men wounded. General Ord mentioned in his official report as worthy of notice for gallant conduct Colonel Jackson, and Captains Dick and Galway, and recommended a list of seventy-one officers and privates “for reward for their gallant conduct.”

Upon the return of the regiment to camp it was ordered to erect permanent winter quarters. The ground was unfavorable, but by thorough draining and grading the quarters were made comfortable. The winter passed with the usual routine of duty and schools of discipline, and without any further collision with the enemy beyond occasional picket rencounters. On the 15th of March, the regiment broke camp and marched to Falls Church, where it met the entire division, and thence turned back towards Alexandria, the enemy for whom the army was in search having withdrawn from its position at Manassas. It finally halted at Bailey’s Crossroads. The camping ground here was unpleasant and the water bad. The Reserves were now attached to the corps commanded by General McDowell, under whom they remained until they were ordered to the Peninsula. After remaining some time at Bailey’s, the regiment moved to Manassas and occupied quarters vacated by the enemy. On the 18th of April, it moved to Catlett’s Station, where it encamped, the whole division is again united. Remaining until the first of May it was ordered to move in the direction of Fredericksburg and arrived at Falmouth on the 4th. While here Colonel Jackson was ordered to take charge of the parties detailed to rebuild the bridge which the enemy had fired and destroyed when he withdrew.

Preparations were made by McDowell’s Corps for marching overland to join the army operating in front of Richmond, and the cavalry and a portion of the Reserves were already on the way; but the appearance of a heavy force of the rebel army in the Shenandoah Valley under Jackson, rendered this movement impracticable. A part of McDowell’s Corps was retained for the protection of the Capital, and the Reserves were ordered to proceed to the Peninsula by water. In compliance with this order the Ninth broke camp on the 10th of June, and embarking on the steamer Georgia, proceeded to the White House, whence by easy marches it moved to Mechanicsville, arriving on the 19th. Here the division was assigned to the corps commanded by General Fitz John Porter. On the morning of the 20th, the regiment was ordered on picket duty, and was posted along the Chickahominy, within speaking distance of the rebel lines. For three days it remained in position without relief, and on the 23rd was under arms until one o’clock P. M., when it was ordered to Mechanicsville. The noise of the enemy at work in a thick wood, concealed from view, excited apprehension. Accordingly, companies C and G were ordered to cross the creek and ascertain the purpose of their activity. A sharp skirmish ensued, in which the enemy was driven back to his reserves. The two companies then retired and rejoined the regiment with a loss of one wounded.

On the 26th of June, the Ninth took part in the battle of Mechanicsville and was stationed, in the early part of the battle, in support of the Third Brigade, much exposed to the enemy’s fire. Later in the day he commenced massing his forces on our left when the Ninth was marched by the flank and took position to the right and partially in support of the Twelfth, where it maintained itself with unwavering ranks under heavy and continuous fire. During the succeeding night, it was placed on guard in position stretching from our rifle pits to the river, and on the following morning was left to cover the withdrawal of the division to Gaines’ Mill. This difficult duty was successfully executed in broad daylight, in face of an enemy stung to madness by the bitter repulse of the previous day. “In fine,” says General M’Call, in his official report of this battle, “our killed had been buried, our wounded had been sent off by seven o’clock A. M. on the 27th, and not a man, nor a gun, nor a musket was left upon the field. The regiments filed past as steadily as if marching from the parade ground.”

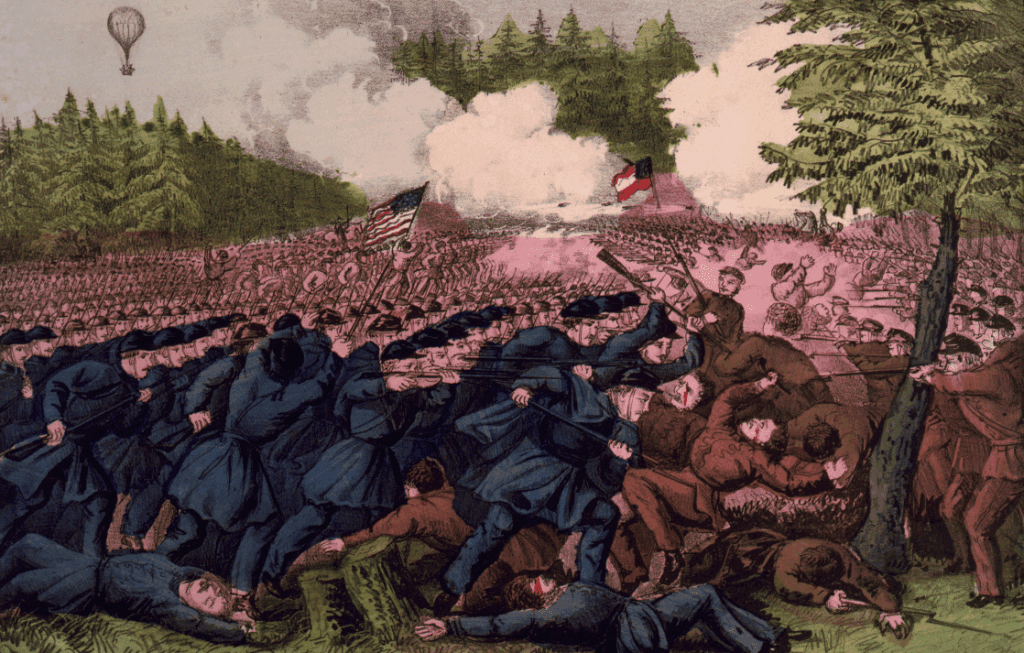

Porter’s Corps was drawn up in the battle line at Gaines’ Mill, and the division, as it arrived, was posted in the rear, as a reserve. By two o’clock P. M., the enemy had attacked along the whole line, and by four o’clock the entire second line and reserves had been brought into action and were desperately engaged. The Ninth was ordered to the support of the Sixty-second Pennsylvania and the Ninth Massachusetts regiments. With difficulty it passed a swampy ravine on its way, raked by the fire of the rebel infantry; but it reached the designated position in good order, and the three regiments were commanded to charge the enemy, now glorying in his strength, and pressing forward with confidence. The charge was successfully made; but advancing too far in pursuit of the retreating column, they were in turn countercharged, attacked in flank, and were obliged to yield the ground so gallantly won. Re-forming, they, again and again, returned to the onset, but were unable again to move him from his position, though they held their ground, and at night retained their place in the front line.

Retiring across the Chickahominy during the night, the Reserves two days later commenced the march across White Oak Swamp towards the James River. After crossing White Oak Creek, General M’Call was ordered to take a position at the junction of the New Market, Charles City, and Quaker roads, to repel any advance of the enemy from the direction of Richmond. The disposition was accordingly made, facing to the right flank, with Meade’s Brigade on the right, Seymour’s on the left, and Reynolds’, now commanded by Colonel Simmons, in reserve. In front of the line of infantry, Randall’s Battery was stationed on the right, Cooper’s and Kern’s opposite the center, and two German batteries, Deitrich’s and Kennerheim’s, on the left. The Ninth Regiment was posted in support of Cooper’s Battery. At half past two P. M. the pickets were attacked, and at three the battle opened in earnest. The left flank being exposed, the enemy sought, by attacking in heavy force, to turn it. To avert the threatened disaster, the Fifth and Eighth, under command of Colonel Simmons, were sent to support it, and by obliquely to the left, to meet his advance. But the great superiority of his numbers enabled him to mass his troops on all points of our line, and while the attempt upon the left was in progress, attacks were simultaneously made upon the center and right. Cooper’s Battery was repeatedly charged, and at each time by fresh troops, but they were as often swept back by the deliberate fire of the artillery and the steady fire of the Ninth. During a short interval when this regiment was withdrawn to support a regular battery on the left, Kern’s Battery having fired its last charge, and failing to receive a supply, was forced to withdraw. The enemy seeing this became emboldened, and made a determined charge upon Cooper’s Battery, capturing it. At this juncture, the Ninth returned to its place and finding the guns lost, charged upon and re-captured them. In this charge William J. Gallagher, of Company F, captured the standard of Tenth Alabama, killing the rebel color bearer.4 Earlier in the battle, when the enemy had advanced within a few feet of Cooper’s guns, the Ninth charged and drove him back at the point of the bayonet to his second line, where the fight became terrible, and one of his standard-bearers fell badly wounded. On seeing it, William Tawney, of the company I, rushed forward and caught up the flag, carrying it back into our lines. As the command fell back over the ground which had been held by the Seventh Regiment, and on which its flag had been dropped, seeing it, this same William Tawney rushed forward through a storm of bullets and caught it up, carrying both flags off the field.

The most desperate fighting the Ninth had yet experienced was on this hotly contested field, and though the Third Brigade was terribly shattered, the division held its ground against vastly superior numbers, successfully protected the road on which the immense trains were moving, saved the two wings of the army from being separated and destroyed in detail, and withdrew from the field in good order and in its own good time.5

Falling back to Malvern Hill, it was assigned a place in reserve and was under fire from the enemy’s artillery, but not actively engaged. During the following night, it moved with the entire army to Harrison’s Landing, where supplies awaited its arrival, and where it enjoyed a few days of much-needed rest. Here the army occupied an entrenched camp, secure from attack, and the line of supply was well assured. The enemy subsequently moved some light batteries to the right bank of the James, and succeeded in throwing a few shells into it, but was soon driven away, and a picket line was established so as to completely shield it from future attempts. The Ninth, together with the Tenth and Twelfth regiments, were engaged in this duty. As the troops advanced, the enemy, together with the inhabitants, for a radius of three miles around, withdrew, leaving the district clear. Details were established to guard the new line, and the Ninth remained engaged in this duty until the 16th of August. In the meantime, the Army of the Potomac had withdrawn from the Peninsula and was proceeding to join the Army of Northern Virginia, under General Pope. The Reserves were the last to leave and embarking upon transports moved up the Potomac to Acquia Creek and debarking, thence marched to Falmouth Heights. Resuming the march after a brief halt, they moved via Kelly’s Ford, through Rappahannock Station, Warrenton, New Baltimore, and Hay Market, to meet the right wing of the rebel army under Jackson, in the vicinity of Manassas Junction. This forced march of five days without adequate supplies of provisions, with the enemy hanging on flank and rear, proved one of the most exhausting which it was ever their lot to endure.

On the 29th of August, the division arrived in the neighborhood of Groveton, and on the afternoon of that day, a rebel battery was discovered posted on its left, six hundred yards away. The Ninth and Tenth regiments were ordered to reconnoiter the ground and ascertain the enemy’s strength and actual position. When within one hundred yards of his lines it was found that his guns were supported by a large force of infantry, which opened a murderous fire upon them, and from which they withdrew under cover of our guns. A stronger force was then sent forward when he hastily abandoned the ground. On the 30th, the regiment was on the extreme left flank of the division and of the union line. Very soon after the battle commenced the enemy outflanked us on the left and gave the Ninth an enfilading fire which inflicted most grievous injury; but notwithstanding this, it was the last to leave the line, and the withdrawal was executed in good order. It re-formed under cover of Cooper’s Battery, where the Third Brigade was posted for its support. Orders were soon received to fall back to a point five hundred yards to the rear, and re-form, but were scarcely executed when the line in front gave way, and it was ordered to retire across Bull Run. Here the regiment reformed under command of Colonel Sickel, the senior officer of the division on the field, under whose orders it marched to Centreville, arriving at ten o’clock P. M. The battle was disastrous to our arms, and particularly so to this regiment, losing heavily on account of its exposed position. Not the lack of valor on the part of the brave men here engaged, but a want of harmonious composition and movement of the army, made the result of the great slaughter and the hard fighting, vain.

Previous to entering this campaign Colonel Jackson had been promoted to be a Brigadier General and had been assigned to the command of the Third Brigade, the command of the regiment devolving upon Lieutenant Colonel Anderson, who has subsequently commissioned Colonel, to date from 15th of July, 1862. During the battle Colonel Hardin, who was commanding the brigade, in the absence of Colonel Jackson, was wounded and carried from the field, when Colonel Kirk, of the Tenth, assumed command, who was also wounded, and Colonel Anderson succeeded him, and Major Snodgrass succeeded to the command of the regiment.

On the evening of the 31st, the Third Brigade was ordered to picket, on the Cub Run Road, leading to Centreville. Marching a mile out, it was posted by regiments at short intervals, with sentinels advanced, who were enjoined to observe strict silence, as the enemy still occupied a threatening attitude. At one o’clock A. M., it was re-called, and marched to the neighborhood of Chantilly, where it halted until daylight, and was moved about during the day, without coming to an engagement, until five o’clock P. M., when the division was hastily formed in solid columns of regiments by brigades, and the battle raged furiously until dark. The regiment bivouacked on the field where it fought, and on the following morning retired to Arlington Heights.

A little more than four months before, the Ninth had left this neighborhood a strong regiment, full of vigor and buoyant with hope; it was now again upon the same ground, reduced by killed, wounded, and sick to nearly one-half its former numbers, and the survivors worn and exhausted with almost constant marching and fighting; but it was here met with supplies and clothing, of which it was in great need, and after a little rest was again fresh in spirit and ready for the contest with its old foe.

It was allowed but two days for rest, and on the evening of the 3rd of September was again ordered under arms, and that night marched through Washington into Maryland. It proceeded to Monocacy Creek and remained until the morning of the 14th, when the division broke camp and moved in the direction of Turner’s Gap, in the South Mountain, where the enemy was strongly posted, to dispute the passage. Reno had already attacked the left before the Reserves arrived. Meade, who was now in command, was ordered to move by a by-road to the right and attack, and if possible, turn his left flank. After ascertaining the position of the enemy, and that he was occupying the fastnesses of the mountain with infantry and artillery, the proper dispositions were made, and the division advanced to the attack, the Third Brigade being led by Colonel Gallagher of the Eleventh. The ground was steep and rugged, and the enemy disputed every inch with great obstinacy; but the column swept the steep acclivity and triumphantly carried the summit, resting at night, masters of the field. In the heat of the contest, Colonel Gallagher was wounded, and the command of the brigade devolved upon Colonel Anderson, and that of the regiment upon Captain Samuel B. Dick, of Company F, Major Snodgrass being at the time sick in hospital at Washington. In this engagement, ten men were killed, and one officer and thirty-six men were wounded.6

After the battle of Antietam, the regiment moved with the army by easy stages to the neighborhood of Warrenton, where McClellan was relieved, and Burnside ordered to its command. Masking his intentions by a demonstration in the direction of Gordonsville, he moved towards Fredericksburg and commenced preparations for crossing the river and offering battle. The Reserves under General Meade were attached to the First Corps, commanded by General Reynolds. The left wing of the Union army, comprising nearly half of its entire strength, embraced the grand division of General Franklin, to which the Reserves belonged, and a part of the grand division of General Hooker. On the 12th of December, the left wing crossed the river on pontoons and assumed the position in front of the rebel workers. The Reserves were selected for the attacking column. The Third Brigade, under General Jackson, held the right of the line, the First the left, and the Second was posted in reserve. The Ninth regiment occupied a position on the left flank of the division and was thrown forward on the skirmish line. As it advanced near the foot of the hill to the left of the railroad, the firing became very severe, and in compliance with orders it was marching directly by the line when it was ascertained that its supports had obliqued to the right and were out of supporting distance. The regiment then took shelter behind an old fence and ditch, which answered the purpose of rifle pits. Here the men did excellent service picking off the rebel sharp shooters and the gunners from a battery commanding the left flank of the division. This battery had been inflicting terrible slaughter upon our forces, but it was completely silenced by the sure marksmen of the Ninth. This position was held until it was ascertained that the remainder of the division had fallen back to the batteries when the order was given to retire. But as soon as the breastwork was abandoned, and the men were out from cover, a terrific fire from the enemy’s infantry, and from his battery, which had been held in check, was opened upon them. In the meantime, a detachment of his infantry had been moving around to the left under cover of the woods and had gained a position within a short distance of its left flank, ready to dash out and capture it. But the withdrawal was timely and successfully made. The loss was nine killed, twenty-seven wounded, and sixteen taken prisoners. General C. F. Jackson, commander of the brigade, who had led the regiment in its first campaign, and to whom it was indebted for its efficient organization and training, was mortally wounded while in the act of ordering his men to the charge, and about to lead the way.

Shortly after Burnside’s second attempt to cross the Rappahannock and give battle to the enemy, which was arrested by the sudden breaking up of the roads, the Reserves were sent to the Department at Washington to re-organize and recruit their shattered ranks. They were assigned to duty on the Orange and Alexandria railroad, and in the defenses of Washington, and recruiting officers were sent to Pennsylvania for men. Consequently, the regiment was not engaged in the battle of Chancellorsville.

When it was ascertained that the enemy had again crossed the Potomac in June 1863, and was threatening Pennsylvania, the application was made both by General Reynolds, who commanded the First Corps and by General Meade, who commanded the Fifth Corps, to have the Reserves attached to their commands. The application was also made by the officers of the division, and great impatience was manifested by the men to be sent to the field. Accordingly, the First and Third Brigades, under command of Colonels M’Candless and Fisher, were ordered to join the Fifth Corps as it marched past Washington on its way to Gettysburg.

General S. W. Crawford was assigned to the command of the division. Upon the removal of General Hooker, and the succession of General Meade to the command of the army, General Sykes was assigned to the command of the Fifth Corps. On the 2nd of July, Sykes having arrived upon the field, was by Meade’s disposition, placed in reserve in the rear and to the right of Round Top, in support of Sickles, of the Third Corps. When the latter, in his advanced position, was worsted and driven back, and the enemy was about to clutch Little Round Top, which was of great strategic importance, Sykes was ordered forward to stem the torrent of the victorious foe. Having taken a part of his brigade to the summit to the support of Rice’s Brigade, Colonel Fisher hastened back and sent the Ninth Regiment, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Snodgrass, to clear the ground and hold the line between Round Top and Little Round Top, of which the enemy had struggled hard to gain possession, and from which he was only driven by the most obstinate and determined fighting. Having gained the position designated, the line was fortified with the loose fragments of granite which lie scattered in profusion on the rugged sides of the mountain and was made secure against attack. This part of the line immediately fronted the “Devil’s Den,” in which the enemy’s sharpshooters took refuge, and from which they could not be dislodged. The loss in this battle was six wounded.

The regiment joined with the army in the pursuit of Lee, as he withdrew towards Williamsport, which resulted in driving him beyond the Potomac without a further contest. Receiving fresh supplies of clothing, and after resting for a few days, it again entered Virginia and took part in the maneuvers of General Meade to again bring the rebel chieftain to battle, which finally culminated in the expedition to Mine Run, where the former wisely declined to fight, after facing and thoroughly reconnoitering his antagonist’s position. During the remainder of the winter, the Reserves rested in comfortable quarters, recruiting their depleted ranks and preparing for the spring campaign.

On the very day that the campaign was inaugurated, and while standing in the front line in the Wilderness ready for battle, orders were unexpectedly received for the regiment to return to Washington. The term of service had expired, the first of the Reserve regiments, and quitting the field on the 4th of May, it proceeded to Harrisburg, and thence to Pittsburg, where it arrived on the 8th, and on the 13th was mustered out of service.

1 Organization of the Third Brigade, Colonel John S. M’Calmont, Pennsylvania Reserve Corps, General George A. M’Call. Tenth (39th) Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, Colonel John S. M’Calmont; Sixth (35th) Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, Colonel W. Wallace Ricketts; Ninth (38th) Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, Colonel Conrad F. Jackson; Twelfth (41st) Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, Colonel John H. Taggart.

2 Colonel Jackson’s Official Report.–Ex. Docs., II. R., No. 59, p. 5.

3 General Ord’s Official Report.–Ex. Docs., II. R., No. 59, p. [illegible, 3 or 5?].

4 EXTRACT FROM THE TESTIMONY OF GENERAL M’CALL, BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE CONDUCT OF THE WAR.–Just before sunset, about seven o’clock P. M., at least two hours after Hooker reported my whole division completely routed, Cooper’s Battery, in front of the centre, was, after several charges had been repulsed, finally taken by the enemy, but only to be re-taken by the Ninth Regiment in a most glorious charge, wherein the standard of the Tenth Alabama was captured by private Wm. J. Gallagher, of company F, who killed the rebel color bearer and seized the standard, which he presented to me on the ground.–Conduct of the War, part 1, page 588.,

5 TESTIMONY OF GENERAL M’CALL.– * * * I have no desire to treat lightly the reverses on both flanks of my division in this hard fought field; they were the almost inevitable results of greatly superior numbers impelled on those points with great impetuosity. But the Reserves, AS A DIVISION, although terribly shattered, were never defeated, but maintained their ground, with these exceptions, for three hours against thrice their numbers in, I believe, the hardest fought and bloodiest battle in which they have ever been engaged; and in this opinion I am sustained by most of those, if not all, with whom I have conversed. Had my division been routed, the march of the Federal army would certainly have been seriously interrupted by Lee forcing his masses into the interval. The battle being, in fact, over when I was taken prisoner, I was conducted at once to Lee’s headquarters. Here Longstreet told me they had seventy thousand men bearing on that point, all of whom would probably arrive during the night. And had Lee succeeded in forcing M’Clellan’s line of march, they would have been thrust in between the right and left of the Federal army. Under this very probable contingency, had I not held my position, the situation of the divisions on the north of the New Market Road would have been critical indeed. But Lee was checked; and the rear divisions, together with the Reserves and others, moved on during the night, and joined M’Clellan at Malvern Hill before daylight. What share my division had in effecting this happy result, let the country judge. —Conduct of the War, part 1, page 588.

6 A most singular fatality fell upon the color bearers of this regiment. Sergeant Henry W. Blanchard, who had carried the regimental colors through all the storms of battle in which the regiment fought, was a most remarkable man. He had the most complete control of his feelings; in the fiercest hours of battle, was always perfectly calm, never shouted, cheered or became enthusiastic, but steadily bore up his flag. At the battle of New Market Cross Roads, when every color bearer in the division was either killed or wounded, Sergeant Blanchard received a wound in the arm, he retired a few minutes to have his wound bandaged and then returned to his place. At Antietam he was so severely wounded that the flag fell from his hands, and he was unable to raise it; Walter Beatty, a private, seized the banner to bear it aloft, and almost immediately fell dead, pierced by rebel bullets; another private, Robert Lemmon, took the flag from the hands of his fallen comrade, a companion calling out to him, “don’t touch it, Bob, or they’ll kill you,” the brave boy, however, bore up the banner, and in less than a minute lay dead on the ground; the colors were then taken by Edward Doran, a little Irishman, who lying upon his back, held up the flag till the end of the battle, and for his gallantry was made a non-commissioned officer on the field.–History of the Reserve Corps, Sypher, p. 391.